As the first day of school nears, unresolved crises at L.A. Unified loom. In May, Superintendent Alberto Carvalho attempted to redeploy on-campus police officers to 20 schools in the district. Carvalho’s attempt was largely unsuccessful – police were only installed at two school campuses – but the desire to revert to policing still lingers.

In 2020, after a concerted campaign by Students Deserve and the Police-Free LAUSD coalition, permanent police officers were removed from L.A. Unified campuses, and the Los Angeles Schools Police Department (LASPD) budget was cut by $25 Million. The funds were diverted to programs and positions that would better support the mental and emotional health of students and provide alternatives to policing.

Responses to school safety at LAUSD, whether from news outlets or board members, have tended towards a particular narrative: the absence of school police has made L.A. Unified schools unsafe.

This claim began to proliferate almost immediately after the LASPD budget was cut. Even without the $25 Million, police still capture a large part of the district’s safety budget. LASPD remains the largest school police force in the country.

Students Deserve, a coalition of students, teachers, and parents, led the movement resulting in the largest divestment from school police in the country. They have also successfully campaigned for an end to random searches and the use of pepper spray on students.

“There is no evidence in LAUSD’s history or other school districts that proves that the presence of school police makes campuses safer,” Students Deserve director Joseph Williams told Westside Voice. “In fact, there are some studies that suggest that the presence of school police has actually contributed to making outcomes of on-campus safety incidents worse, especially when those incidents involve Black students and other students of color.”

Maki, a rising senior at Dorsey High School in the Westside’s Baldwin Hills and a Students Deserve member, said the removal of on-campus police has made him feel safer and more comfortable at school. When Maki attended Audubon Middle School, school police conducted searches at random, “Dumping everything out of our bags in search of ways to get us arrested,” he said. Students of color make up more than 95 percent of students at Audubon. “We felt criminalized for just attending school,” Maki added.

Despite their victories, members of Students Deserve told Westside Voice the district has made little progress in funding and implementing alternatives to policing.

Dorsey High School is one of the few schools in the district that has introduced community-based safety (CBS) programs. The district defines CBS as an approach to public safety enhancements that “Actively involves the community, regards violence as a public health issue, sees criminalization and incarceration as ineffective and harmful, and seeks to strengthen the ‘social determinants of safety,’” like access to affordable housing and economic mobility.

The CBS plan was approved by the Board in 2023, but the district’s Independent Analysis Unit reported the pilot program was not using all of the funds allocated, was understaffed, and was not effectively including the community in the process.

At Dorsey, Maki said only two people staff the school’s Safe Passage program. Safe Passage programs have been introduced at 41 schools to help students travel to and from campus safely. Dorsey has nearly 800 students. The district, Maki said, has thus far implemented CBS sparsely and slowly, leaving one or two workers responsible for hundreds of students.

Romy, a rising senior at Eagle Rock High, said her school hasn’t introduced any alternatives to policing. Eagle Rock High is one of hundreds of schools that isn’t a part of the CBS plan. “The district has been failing students,” she said. “The district needs to prioritize partnering with our communities instead of cops who harm and frighten our students.”

Underlying all of the urgency surrounding the school police is the district’s reports that fights, drug use, and threats have risen since 2021. Nationally, behavioral issues at schools have increased since students returned after pandemic closures. Most reporting and research attribute the troubling upward trend to the effects of the pandemic – schools reported higher rates of violent and non-violent incidents whether they had police in schools or not.

And though some pro-police groups are utilizing district reports to call for the refunding of the LASPD, inconsistent reporting practices may undermine the district’s credibility in identifying and mediating school safety issues.

L.A. Unified incident data is not easy to find – the School Safety and Climate Committee recommended the district publicly share monthly incident reports for better transparency and responsiveness. The Incident System Tracking Accountability Report (iSTAR), an interface that allows principals and administrators to file incident reports, is the primary source of school incident rates along with LASPD reports. In an April presentation to the School Safety and Climate Committee, Director of the Division of School Operations Alfonzo Webb presented seldom-seen numbers on district-wide incidents over the last seven school years.

A table of data showed incidents of fighting and physical aggressions, threats, illegal and controlled substances, and weapons increased significantly from the 2021-22 school year onward. Fighting and physical aggression, Webb reported, had more than doubled since 2017-18.

But these numbers do not match reports previously released by the district. In the 2017-18 iSTAR report, there were 3,461 incidents of fighting or physical aggression. This year, the district said 2017-18 had just 2,270 incidents in the same category – 800 fewer incidents than originally reported. All of the other incident categories show the same differences. The 2017-18 iSTAR report listed 2,479 threat incidents. The April report said there were only 1,994 that year – 500 less than first reported. Comparing the 2018-19 iSTAR report to the April report reveals similar inconsistencies.

An analysis from the district’s Independent Analysis Unit said “A perceived increase in violence on District property” reported by news outlets in 2021 prompted a review of incident rates in Fall 2019 and Fall 2021. They found that safety-threatening incidents “Remained relatively stable” when comparing the two periods.

But the April report is not just misaligned with reports from years ago. Just last September, incident data from the Division of School Operations varied widely from the figures reported in April. In September, the district said 2021-22 incident rates were much higher than they were reported to be in April. In September, the district said there were 3,954 incidents of fighting and physical aggression in 2021-22. In April, the district reported there were only 2,965 – the difference of almost one thousand less incidents.

The April report from the district showed a dramatic uptick in incidents after students returned to police-free schools in 2021. However, according to the original iSTAR reports, the increase is far less pronounced.

It is unclear why there is so much variability between these reports. Alfonzo Webb and the Division of School Operations did not respond to questions from Westside Voice. Where this data was collected and why it was adjusted is unknown.

Williams said L.A. Unified has often withheld or misrepresented data that undermines policing practices. When Students Deserve and the Students Not Suspects coalition were campaigning to end random searches, L.A. Unified said the searches were necessary – police were finding guns on students. ACLU SoCal and Students Deserve filed a Public Records Act request with the district. “In these thousands of pages of data from incident logs of random searches that we analyzed, we found zero guns. There was not a single incident of LAUSD finding a gun due to a random search,” Williams said.

Students Deserve and allied organizations have faced similar years-long battles for records access that eventually proved LASPD was disproportionately targeting students of color. “Because of that history, it does not seem far-fetched to me that people within the district would either manipulate or lie about data or twist data to push a narrative,” Williams said.

With just a cursory look at the district iSTAR reports, Williams said he couldn’t draw a firm conclusion on the incident reports but marked differences between the raw data and the reports would not surprise him. “Would that be out of the ordinary or breaking with past practice for folks within LAUSD? Unfortunately, no.”

The April report spurred heated discussion at subsequent board meetings. In June, District 1 Boardmember George McKenna, who represents a portion of the Westside, declared the police budget should be increased to its pre-2020 levels. District 3 Boardmember Rocio Rivas questioned the implementation of community-based safety and restorative justice practices.

The Board unanimously voted to approve the CBS pilot program, “But during the process of making this a reality, some of the board members showed that this is something that they are at least partially against,” Maki said. The difference in word and deed has become clear to Maki and Romy as they’ve seen the district make little, if any, progress in fulfilling their duty to keep students safe.

The board remains divided and the potential for a reactionary district response presents an acute threat to advocates for community-based safety in L.A. Unified.

“The stakes are extremely high,” Williams said. “With growing authoritarianism at the local, state, and national levels, there have been corresponding calls to increase the surveillance, criminalization, and policing of Black and Brown young people in and outside of schools,” With austerity policies bearing down on the district, “Schools are at a high risk of losing critical resources like counselors, school climate advocates, vice principals and more – all while a small minority of adults vocally advocate for cops to be returned to campuses. This is creating the conditions for even more young people to be criminalized in schools instead of being provided with care and support.”

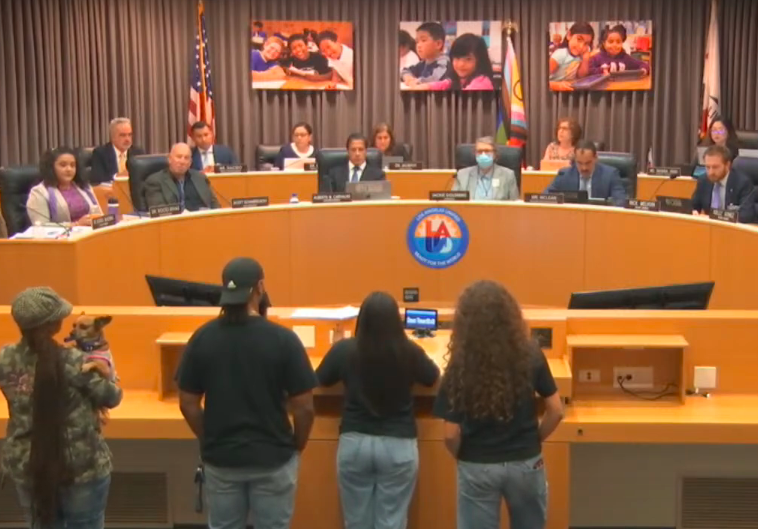

Photo using Screen Capture of Students Deserve members addressing the LAUSD Board.

Stay informed. Sign up for The Westside Voice Newsletter

By clicking submit, you agree to share your email address with Westside Voice. We do not sell or share your information with anyone.