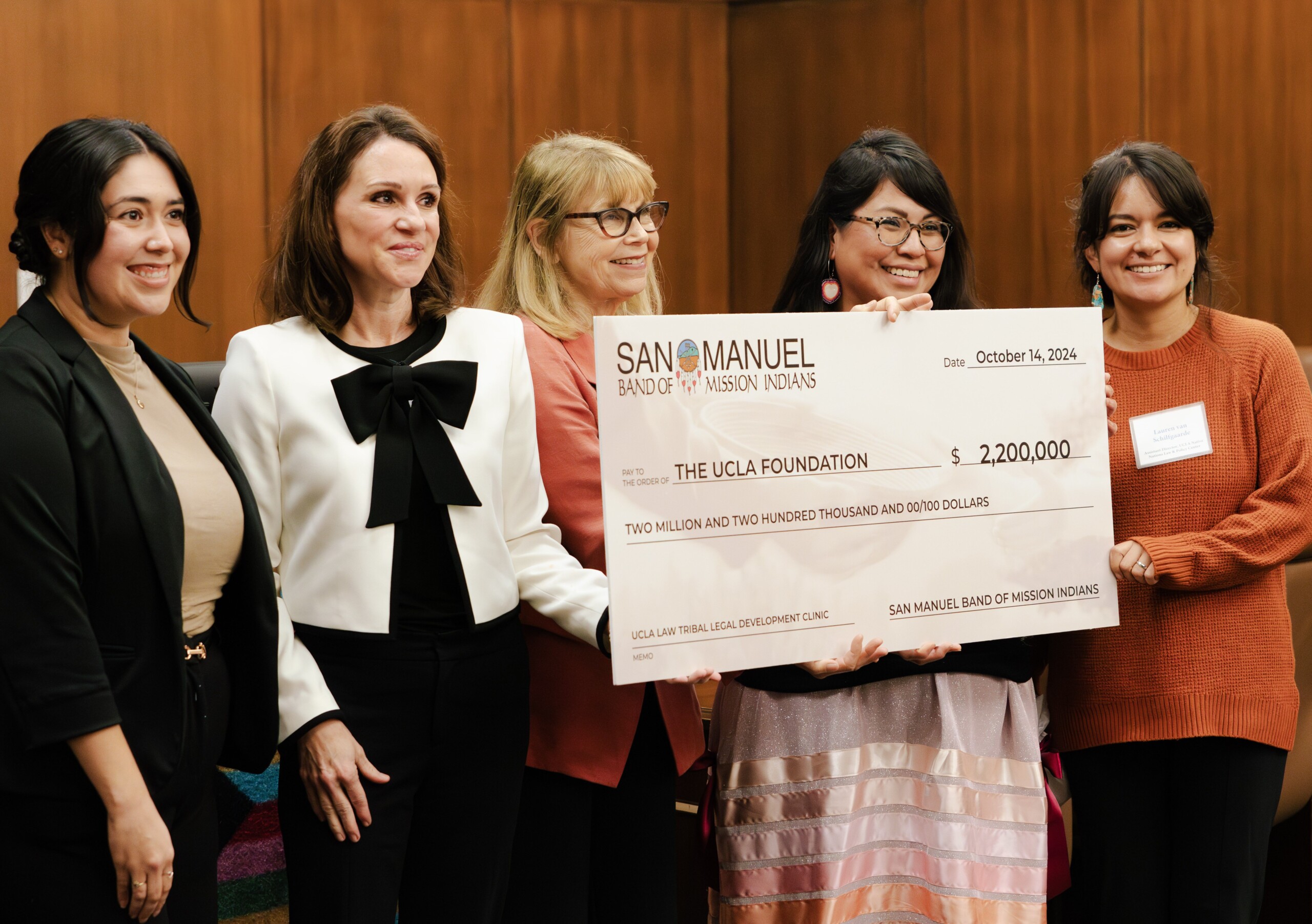

A new $2.2 Million grant from the San Manuel Band of Mission Indians (SMBMI) will bolster the Tribal Legal Development Clinic (TLDC) at the UCLA School of Law’s Native Nations Law and Policy Center (NNLPC), enabling the clinic to continue its work providing free legal services to Native American tribes locally and abroad and “training the next generation of lawyers in Indian law.”

The NNLPC hosted a guest lecture honoring the San Manuel Band of Mission Indians on Indigenous Peoples’ Day this Monday.

The Tribal Legal Development Clinic, founded in 1996, has received more than $7 Million from the San Manuel Band of Mission Indians in the last 20 years. With these grants, the clinic has grown, and in turn, has been able to take on more projects and clients.

Last semester, students worked with four California tribes and four tribal organizations, including the Bishop Paiute Tribal Court and California Tribal Families Coalition.

Students at the clinic work with tribal governments and organizations to draft governing documents, statutes, and codes, build procedures and court infrastructure, and create training materials. A guiding aim of the clinic is to develop model legal practices that can be adopted by other Native nations. The variety of work available to law students at the clinic is wide-ranging. The clinic has provided services concerning repatriation and cultural resource protection, family law, environmental law, restorative justice, and civil and criminal procedures.

“San Manuel views this investment in the Tribal Legal Development Clinic as critical to strengthening sovereignty for all tribal nations,” said Lynn Valbuena, chairwoman of the San Manuel Band of Mission Indians.

Carole Goldberg, who developed the Tribal Legal Development Clinic as a law professor at UCLA, thanked the San Manuel Band of Mission Indians for their generosity and leadership, acknowledging their history of making “contributions that extend beyond [their] own community to benefit Indian Country more broadly.”

“San Manuel understands that tribal sovereignty in Indian country is as strong as its weakest link,” she said.

The clinic was founded with the belief that the university couldn’t adequately train lawyers to enter the field unless they had experience working in collaboration with communities, providing needed services, and benefitting “immensely from the knowledge of elders and culture bearers,” said Goldberg.

Dorothy Alther, the legal director at California Indian Legal Services (CILS), gave a lecture to UCLA law students on Monday about the history of Indian law and the current landscape for law students hoping to join the field.

Alther, a member of the Oglala Sioux tribe, has decades of experience practicing Indian law. She grew up near the town of Wounded Knee on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation and was a high school student when members of the Oglala Sioux tribe and American Indian Movement (AIM) staged the historic occupation of the site in 1973. The occupation “brought about a new understanding of being an Indian,” she said.

That eventually brought her to work in California, where she saw a great need for legal services and broader support for establishing and sustaining tribal courts and law enforcement agencies.

SMBMI established its own tribal court in 2009. Tribes in California operate under Public Law 280, a law passed in 1953 and enacted without tribal consent, that gives certain states shared criminal and civil jurisdiction over Indian Country. The law does not revoke the ability of tribes to write their own laws or establish their own courts and law enforcement agencies, and it does not give the state regulatory powers, but it has hampered the progress of tribal judicial systems in states where it was enacted. There are 109 federally recognized tribes in California and 27 tribal courts, a number that has increased significantly in the last two decades.

In 2009, Goldberg said the establishment of tribal courts “reinforces the legitimacy of tribal governments both internally and in the eyes of outsiders.”

Alther stressed that Indian law is based on tribal sovereignty. She explained that although the Supreme Court has upheld vital laws like the Indian Child Welfare Act in recent rulings, an argument written in favor of the decision by Justice Brett Kavanaugh included the aside that perhaps the landmark law would be declared unconstitutional if another challenge was brought to the Supreme Court in the future.

Supreme Court cases all start somewhere, she said. The local courts are where much of the struggle lies. “That’s what you do as an Indian lawyer,” she said. “You spend a lot of time educating people, and not just in courts.”

The local work is just as critical as the cases that advance to the national courts, especially when higher courts might act to challenge the legal status of self-governing nations. This is despite that status being upheld by treaties, the U.S. Constitution, and case law. The Tribal Legal Development Clinic is one piece of a larger system that depends on collaboration and a mutual exchange of resources, whether financial, institutional, or otherwise.

The Serrano people of San Manuel are indigenous to the San Bernardino region. SMBMI has donated more than $400 Million since 2003 to support education, health, and culture in the Inland Empire and further afield. State Assemblymember James Ramos is a member of the Serrano tribe and served as the chairman of SMBMI. Earlier this month, a bill authored by Ramos was enacted. AB 1812 will require California schools to teach students about the history of Native Californians during Spanish colonization and the Gold Rush and the perspective of Native Californians, a history which hasn’t, until now, been uniformly taught in classrooms statewide.

Photo courtesy of Tiffany Melendez.

Stay informed. Sign up for The Westside Voice Newsletter

By clicking submit, you agree to share your email address with Westside Voice. We do not sell or share your information with anyone.