When Inglewood Unified School District (IUSD) announced the closure of five schools last week, most were angry but few were surprised. District administrator James Morris stated that the closures were due to low enrollment rates, but that didn’t stop students from affected schools from staging walkouts.

Community members say the root of the issue lies in the state receivership the district has operated under since 2012. This receivership is made possible by Senate Bill 533, a law that requires that school districts give up their elected leadership and the democratic process that they depend on in exchange for an emergency loan. For 12 years, IUSD has been repaying the 29 Million dollar loan with interest. They are on course to fully repay the loan in another 10 years. But until they repay and meet the standards of an external evaluating board, Inglewood Unified will not have control of their district. Many feel the district won’t recover without community control.

The California Public Schools Sovereignty Act could restore control to school districts under receivership. The Statewide Coalition for Local School Control has brought the new bill to the state legislature after struggling to be heard by state and local leaders. They are currently looking for a legislator to sponsor it. They want public school districts that accept loans from the state to have the same freedoms as other organizations. What California has now, they argue, is a system that penalizes majority Black and Brown districts.

Fre’Drisha Dixon, an attorney and coalition leader in Inglewood compares the receivership system to other loans the state offers. “When a city takes a loan from the state, the city is just given the ability to pay it back off. They’re not given trustees. They’re not given administrators. They’re not having their legal rights, authority, and control taken away. But for some reason, when it comes to our school districts, which are our government entities, just like the city is, they’re deciding to take the legal rights, the authority, and the control of the school district, so completely stripping our communities of democratic representation,” said Dixon. “We’re not asking for much, we’re asking for equality.”

Beyond the legal case for equal treatment, critics say the receivership hasn’t delivered on its promises. The last 12 years have been disastrous for IUSD. Inglewood organizers with the Statewide Coalition for Local School Control contend that the receivership has done little but restrict community input and consign Inglewood to perpetual failure and instability. Dixon says the state takeover created the IUSD’s problems. “It’s no coincidence that our school district is declining, it is a direct reflection of its management,” said Dixon. “What have you done in 12 years?”

In the 12 years of receivership, the district has had 10 outside-appointed administrators running things. The elected IUSD School Board, which voted against the five school closures last week, is merely an advisory board. While the district had millions of available funding set aside for badly needed facility repairs and renovations, the Fiscal Crisis and Management Assistance Team (FCMAT) – the external auditor for districts under receivership – noted the planned improvements had been delayed significantly by leadership turnover.

IUSD’s enrollment dropped by a third in the first decade under state control. Districts across the country, and even in neighboring LAUSD, have seen enrollment drop due to changing demographics. As the district cut funding for after-school programs, laid off staff, and slashed teacher pay students suffered. Parents concerned about the quality of education moved to other districts. Dixon cited the disrepair of Inglewood’s buildings and the low teacher pay as contributing factors to the district’s enrollment loss.

IUSD’s teacher pay is the lowest in L.A. County. One Inglewood high schooler, Dixon says, told her that the student’s AP Biology class has had a substitute teacher all year. This high schooler wants to be a doctor, but they haven’t learned anything in class. Dixon says the county has no answers for community members who want improvements now. “They don’t plan on making any plans or putting any plans into action until they close the schools that they want to close down,” she said.

The school closures seem to cause more problems than they promise to alleviate. While Morris presents the closures as a neutral consequence necessary to the financial health of the district, the reality is unclear.

Dixon says Morris, in line with previous administrators and local government leaders like Inglewood Mayor Butts, has ignored the community’s concerns over safety and disruption to the students’ lives. The school closures often coincide with school consolidations. The students of a closed school are moved to another one in the district. Students can no longer walk to school with their parents. And in Inglewood, a mile-long difference in school travel creates safety risks.

“People who don’t live in our community don’t understand that gangs are still very prevalent. They are very much still entrenched in our neighborhoods in Inglewood. One block might be this gang and then the next block over is a whole other gang,” Dixon said. “We’ve been able to sign a peace treaty in our community and have things calm, but these folks, their kids go to these schools on this side, and then the other folks go here. We don’t force people to cross paths.” Parents pull their children from the district rather than try to navigate the uncertainty.

The district’s financial struggles seem insurmountable because school funding is based in part on enrollment. What seemed like a lifeline from the state has become a nail in IUSD’s coffin, and the Inglewood community isn’t convinced that it was meant to be anything else.

False reporting and financial mismanagement led to the passage of Assembly Bill 1840 in 2018, a law that moved receivership management from the state to the county level. In 2018, district control moved from the California Department of Education to the L.A. County Office of Education (LACOE).

Three IUSD schools have been closed since 2019. With last week’s announcement, the total comes to eight, a significant portion of the district’s 17 schools. What seemed like neglect on the part of the state’s management now seems calculated in the hands of the county. AB 1840, while moving control over school districts from the state to their respective county education offices, also enabled counties to sell and lease school district land.

For Dixon and other organizers with the Coalition for Local School Control, the motivations of their local administrators are obvious. Inglewood has been a target for developers looking to extract enormous amounts of capital from the city, and the majority Black and Brown IUSD is especially vulnerable without community control. Dixon said state receivership can happen to any district that needs a loan, but stated they are “Only taking over school districts that have Black and Brown School Boards and serve a Black and Brown community.”

Every school district in California that has been put under receivership has had a majority Black and Brown student population. By fleecing these districts, whether through mismanagement or calculated profiteering, Dixon said the damage to public education ensures that students won’t become doctors or lawyers, but instead become low-wage laborers for the entities that have bought up their city.

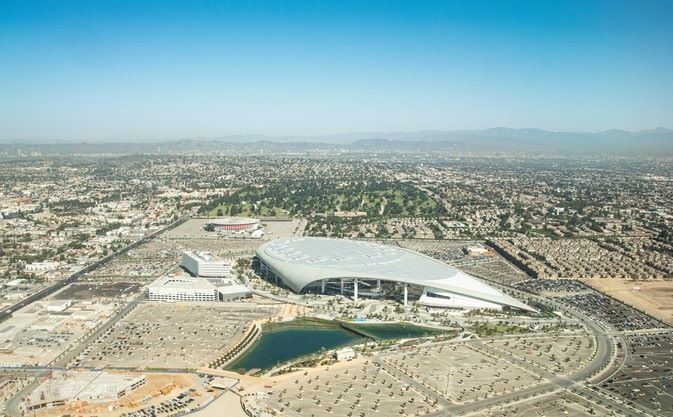

The arrival of SoFi Stadium and the Intuit Dome, together worth more than $7 Billion, were warmly greeted by Inglewood Mayor James Butts. Critics say his coordination with current IUSD Administrator Morris has created an environment where corporations are embraced publicly to the detriment of the city’s residents. One of the Inglewood schools slated for closure, Morningside High School, is less than a mile from the sports complex that houses SoFi and Intuit. Last year, the district agreed to sell land adjacent to Morningside and Clyde Woodworth Elementary. Morningside High was one of the schools slated for closure in last week’s announcement while Woodworth Elementary was closed last year. “We can easily connect the dots in Inglewood, right?” Dixon said. Mayor Butts “Has a relationship with corporations. We know that Administrator Morris – his job is to close the schools so that they can sell and lease the land. That’s why you see Mayor Butts and Administrator Morris hand in hand during press conferences.”

James Morris maintains that school closures are financially necessary. In a speech announcing the closures, Morris said “We’re operating more schools than we can afford to operate.” He acknowledged the community’s concerns but argued that the community had been reasonably included in the discussions before his decision. He also announced plans to reconstruct Inglewood High, using $200 Million to create a “Breathtaking, brand new, state-of-the-art campus.” Morris has also commented that some schools are closing for safety reasons, citing the nearby sports complex and future transit hub as “not ideal” neighbors to students.

In their strategic plan for 2022-2025, LACOE noted that “Developing and implementing a facilities consolidation and closure plan” was one of their priorities for IUSD. “We recognize that many of our former educational systems and structures have not worked equitably for students and families, and we do not want to revert back to outdated approaches,” the department said.

In a recent interview on LACOE’s Ed Buzz, Administrator Morris, and LACOE Superintendent Debra Duardo agreed that the district was making progress towards exiting the receivership. Duardo praised Morris’s leadership and his ability to bring the community together. Duardo said in addition to providing staffing and advisory support to IUSD, the department also aimed to inspire hope in the district.

When asked for comment on LACOE’s involvement in the sale of IUSD land and the allegations of racism in the receivership system, LACOE only responded that the questions should be redirected to IUSD.

Inglewood organizers do have hope for the district’s future, though that hope isn’t coming from the county. The California Public School Sovereignty Act is one piece of a larger strategy, refined and amended over the years, to return IUSD to its community. Their opponents are powerful, detached, and well-funded, but organizers know they will find a way through. “The fight isn’t over,” says Dixon.

Photo by johnemac72 on iStockphoto.com

Stay informed. Sign up for The Westside Voice Newsletter

By clicking submit, you agree to share your email address with Westside Voice. We do not sell or share your information with anyone.